Climbing Elbrus

In August 2017 I climbed the West peak of Mt. Elbrus via the South approach. Elbrus is the highest point on the European Continent standing at 5642m and represents the European component of the 7 Summits - a challenge to climb the highest peaks on all 7 continents. It sits in the Caucasus Mountains in Russia and is a stone’s throw from the border with Georgia.

Here’s a quick summary of my experience.

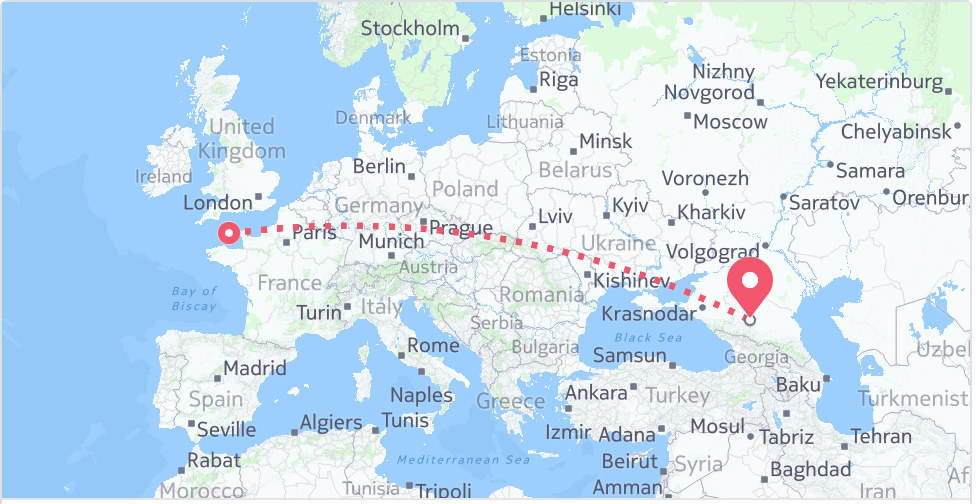

Our tour was organised by Adventure Peaks. We traveled from the UK via Gatwick in to Moscow Sheremevo and then onwards to Mineralnye Vody (MRV). At MRV, we were met by the local travel company who arranged our onward travel via minibus in to the Baksan Valley, which formed our base for the trip.

The trip itself was focused around acclimatisation walks with a window for the summit attempt.

Initial acclimatisation is in the Syltran Valley which is a pleasant hike through lush green mountains. Camp is makeshift in a lower col, next to a large lake. The major acclimation is on Mount Mukal with a summit of 3899m. I’m not going to dwell too much on this because it’s a fairly miserable experience. Mukal itself is a fairly ignominious mountain - a rocky scree. The top does offer some impressive views of the surrounding area, as one might expect, but Elbrus itself is hidden from view. A few days in the area and it was back down to the Baksan Valley to prepare for moving on to the Elbrus ‘base camp’ - the Barrels.

The Barrels are well known. Base camp is accessed by a network of cable cars and ski lifts - the lower areas of Elbrus itself are actually a popular ski resort. The Barrels are a rundown camp on war-era oil barrels - enormous metal canisters that have been adapted for accommodation for 6-8 people, with a few additional facilities such as a portakabin kitchen/mess area and a long drop for toilet facilities.

From the Barrels we did 3 acclimatisation / training walks - although somewhat limited in nature. (1) - Prijutt Refuge, 4060m. (2) - Pastukov Rocks, 4700m. (3) - Lower Level skills such as ice axe arrest work. The issue with the area is that there is little scope to venture laterally from the Barrels - you essentially go up… and come down again. Go up a bit higher… and come down again. The idea is simple - you gradually introduce your body to higher altitudes so that as you go higher and higher you don’t feel the impact of the lower levels of oxygen so much both in terms of physical ability and the impact on your brain function. Even at these altitudes, altitude sickness can be a real problem. I do tend to suffer but also acclimatise well. It’s most easily described as just having a really bad hangover.

For most of the week, our weather was fine; clear and sunny but, predictably, as we got closer to our summit day(s), the weather deteriorated. We had a 3 day window, but the first two days were written off due to weather - snow was an issue; but the high winds near the summit were the real issue.

On the final possible day, the weather at the Barrels was still bad - snowing heavily and cold and it was touch and go. We prepared anyway, and we went to bed early. I struggled to sleep and moreorless got to a point where I’d convinced myself we weren’t going to go and didn’t sleep much. Nevertheless, we got up at 1am to survey conditions to await advice from our guide Vladimir. I think we were all a bit surprised when he said we were going for it - conditions at the Barrels were bad but as you gained altitude it improved and the forecast for the day was good - so a quick breakfast and final preparations and we set out.

From the Barrels you have the option to hike the three ish hours to the Pastukov Rocks (one of the training walks) or, subject to conditions, pay for a snowcat to take you there. Given that we’d already done that part of the trip, and the poor weather at the Barrels, we opted for the snowcat. This was a pretty cool experience in itself; but an hour in the trail of a 600bhp diesel exhaust in the cold, snow and wind and I think we were all pleased to get off and get walking. We were one of the first groups on the mountain in the morning (more on that later) and so we started the long slow trudge up the base of the east peak; aiming eventually for the traverse that took you to the col between the two peaks. Although the route itself is short; it is a lot longer when you’re on it - especially in the dark, snow and wind with only a head torch and the crampons of the person in front of you for guidance. Whilst not physically demanding (assuming you’ve acclimatised), mentally it’s challenging; the pace is slow so it’s a case of putting one foot in front of the other (carefully so as not to spear yourself with crampons…) hour after hour. You set yourself mini targets based on when you expect to break - usually after 1-1.5 hours where you can have some water (more on that later) and a snack of some sort.

Although time dragged bit, we made good progress and we were on the traverse as the sun started to come up. The sun coming up really lifts your spirits, especially in being able to see how far you’ve come. Although seeing how far you’ve got left to go would often dampen them again!

The traverse is long - a lot longer than you think, as you wind your way past the base of the East peak, and start to work up in to the col. A quick break here, and then on to the traverse of the base of the west peak. This was about the only moderately treacherous bit - although there are crevasses if you stick to the route it’s safe; but as you gain altitude on the west peak the exposure does increase commensurately. There are fixed lines in place which you attach in to with lanyards. A couple of the group were starting to feel the altitude so they were then roped to guides for a bit of extra safety.

After 6 hours or so you reach the plateau of the west peak at which point you then have a pleasant 45 minute or so hike up to the summit. There’s a small ridge to reach the summit itself, but the exposure is fairly minimal (compared with stuff I’ve done at much lower altitudes). The summit is unimpressive (as most are) but the views around breathtaking. Wed’ reached the highest point of the European continent!

After a quick congratulation of the team, a personal tribute my friend Simon who I in part completed the climb for and a quick drink, it was time to head back down again. Time was moving on (even though it was barely 9am) but the sun was coming up quickly, and the mountain was getting busier. On the way down you move far more quickly - for obvious gravity-related reasons but also on the high/adrenaline of having done it. But the descent is the most dangerous part of any climb for these very reasons. The way off is simply the same route but in reverse, but by now there is a lot more traffic coming up and some congestion on the fixed lines - and you mostly give way to people coming up.

The final trek back down was uneventful and when we reached the Pastukov Rocks, most of the team elected to take the snowcat back down to the Barrels; myself and a couple of others decided to hike it down which felt like the right thing to do. (I’m still 50/50 if it was!)

From the Barrels we descended all the way to the valley to our hotel for a celebratory beer. We were out on the first flight in the morning - all completely knackered, but in high spirits.

Closing Thoughts

There are a variety of reasons people have for climbing Elbrus. For most it’s the ‘highest point of Europe’ thing - especially if you’re endeavouring to complete the 7 Summits. I had a few reasons; but in reality I suspect few do it for the technical challenge or other mountaineering reasons. Elbrus itself is not a technically demanding mountain - anyone with a reasonable level of fitness, and the mental fortitude to drag yourself up a hill for 12 hours or so and the right gear… could do it. But there are many other mountains around at lower of similar altitudes which are more rewarding, depending on what you’re in it for. Heck, the exposure on Striding Edge on Helvellyn in the Lake District at ‘paltry’ 900-ish-metres is in my mind greater than Elbrus. (This is mostly down to the concept of prominence.)

But nevertheless it’s a fine achievement even if relatively tourist-y. But I remain staggered by the number of people who were woefully underprepared for it - either in completely the wrong kit or who were still at the Rocks on the way up as we were coming down. As we reached the Barrels the weather at the Summit had turned dramatically - with still at least fifty people on it. There weren’t any fatalities when we were there; but there have been in the past (mostly due to wandering off the route down when the weather has changed, missing the route and finding the nearby crevasse field.)

It’s also easy to under-estimate dehydration which I think is a critical contributor to how you feel on the mountain and your likelihood of succumbing to altitude sickness. Even if you’re not thirsty, it’s imperative to keep on drinking water throughout the day - even on the descent. It’s amazing how much your decision making process changes when you’re dehydrated, tired (esp. as the adrenaline wears off) which is why so many issues normally arise on the descent as opposed to the ascent.

Hope this was of help to someone out there considering it - the essence is that if you even think you can do it, you most likely can if you have the right kit, prepare well and have a decent local guide.

The obvious question though… where next!?