Climbing Aconcagua, Argentina

When I posted about climbing Elbrus in 2017 I asked the question “where next” - the literal answer to that question turned out to be Ben Nevis - but the ultimate answer (in terms of climbing big mountains) seems to have become Aconcagua, which I’ve moreorless just got back from.

Aconcagua, in the province of Mendoza in Argentina, and a stone’s throw from the border with Chile stands at 6961m. It is the highest mountain in the Americas, and the highest mountain in the world outside of the Himalayas. It is also the 2nd most prominent mountain in the world.

We ascended the normal route to the North Summit in January 2023 at what seemed liked a very busy time - there were a lot of people on the mountain. Maybe because it’s described as a ’trekking peak’ and ’non-technical’ and ’easy’ by just about anyone you ask which, in my view, is completely wrong. More on that later.

Walking In

The route starts at the bottom of the Horcones Valley. In previous years you might have stayed at and started from Los Penitentes (a few miles down the road) but that whole village has now been sold to the developers building a new tunnel to Chile, so chances are you will have driven in from Mendoza in the morning.

The entrance to the park is where you’ll separate your bags and deposit your main gear with the mulas (mules) who will do the heavy lifting for you. With your permit in hand, you’re faced with a fairly easy walk up the valley to “pre-base camp” - Confluencia - a pleasant 3-4 hour stroll but where you quickly realise you’re starting to gain altitude.

Confluencia is a fairly surprising place - well it is if you haven’t been to a large ‘base camp’ style camp before. Large dome tents are about, as well as sleeping tents, and myriad other things. If you’re with a company outfit, then you will have access to flushing toilets (ish, they’re still longdrops), occasionally hot showers, charging points and even wifi (via satellite internet) that occasionally works!

At this point, it’s all about getting used to being on an expedition and worrying about how your body copes with acclimatisation.

From here, an acclimatisation walk to Plaza Francia is likely, which yields amazing views of the South Face of Aconcagua and sight over both the North and the South summits.

To Base Camp

After a few days in Confluencia, it’s time to continue up the valley - en route to base camp, aka Plaza du Mulas. An 8 hour walk through a devastatingly beautiful and dramatic desert-like valley. The biggest danger here is the heat - and the dust - and the rampaging mulas. Cover up, head down and just get on with it!

The elevation drifts lazily upwards until after a full day of walking and hopefully many litres of water, you arrive at base camp nestled in the bosom of the mountain at around 4300m.

Base camp is a larger version of Confluencia and is the second largest base camp in the world (behind Everest.) The facilities here are a little more rough and ready - the flushing toilets have been replaced by actual longdrops and the showers really do only work occasionally as the source pipes regularly freeze. Away in the distance is the Cuerno (’the horn’) which is easy to mistake for your objective, away to the west is Bonete Peak, and the north-east face (I think) of Aconcagua towers above base camp, giving you plenty to think about as you mill about base camp.

Bonete Peak makes a nice full day acclimatisation walk and achieves over 5000m for the first time on your trip (summit: 5050m), with a lovely short snow ridge at the top and decent views.

Summit push

After plenty of time in base camp and acclimatisation around the area - you’ll be at least 2 weeks in to your trip at this point, it’s time to think about the goal… the summit.

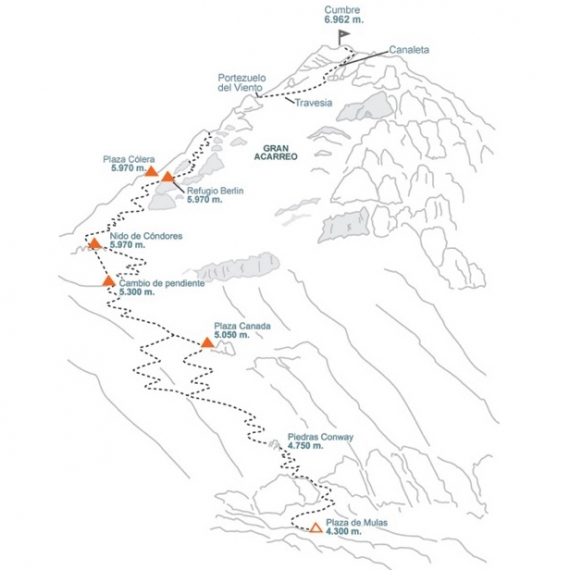

Assuming the base camp medics give you the all clear (at best a cursory check of your vitals), you’ll take more days making your way up the mountain from base camp at 4300m via three separate camps:

- Camp 1 - ‘Canada Place’ - approx 5000m. A reasonably simple day (unless you’re load carrying!) The altitude by now shouldn’t cause you too many problems.

- Camp 2 - ‘Nido de Condores’ - approx 5600m. Approx 3-4 hours from Camp 1. The oxygen is starting to feel a little thin here.

- Camp 3 - ‘Colera’ - approx 6000m. Another reasonably simple day, but your mind can’t help but wander as to what’s ahead of you - Aconcagua is really starting to look like a pretty big hill at this point, and you will now likely be nervously inter-mingled with others preparing for or returning from their summit attempts.

You’ll spend varying amounts of time at each camp based on how you and your group are acclimatising.

Any spare time will be spent trying to not relentlessly contemplate the poor decisions you’ve made and just exactly what the bollocks you’ve got yourself in for.

Summit

Summit day is the big one. That being said, it is not actually quite the same horrible 2am start (with the first 5 hours in the wind, dark and snow) that you get with other summits. The weather is very important, wind especially, but luckily there is no need to be off the summit by a certain time like most other big mountains, which means the start can be somewhat more leisurely. You will still be up early to take fuel and liquid onboard and to get prepped, but there’s no real urgency to get going. We were away by around a lazy 0530 which meant the first 3.5 hours were in the dusky-dark with head torches whilst allowing the sun to rise slowly all around you.

The trick here as with any other large summit is simple: slow and steady wins the race. The mental side of mountaineering really kicks in - you cannot move fast due to the altitude and so you must just find a comfortable all-day left-foot right-foot rhythm and just get in the zone. The route is unwaveringly up, up, up and in most places is very steep.

(The ascent has changed in recent seasons, what used to be mostly rock and bare trails has given way to snow - the snowline is now around Camp 2, so your summit day will almost certainly be 100% crampons. More on this later.)

The ‘shelter’ (not a shelter at all) at Independencia will come - and go - as you continue up. And up. A steep section of many switch backs eventually gives way to the dreaded traverse.

A traverse in usual mountaineering terms means cutting across a face of a mountain, but on a plane… not so on Aconcagua; the traverse cuts under the face but still continues to gain elevation - it’s a steep and narrow path (on snow.) More on this later.

The end of the traverse yields The Cave - which is also not a cave. At best a sheltered spot but it marks the start of the Canaleta - a snowy rock chute that gives way to yet another steep ascent and the last push to the summit. But don’t be fooled that you’re nearly there - even after 7 or 8 hours, you still have at least 3 hours of ascent ahead of you.

See this off, though, and other than one last desperate rock step to navigate with crampons and a fuzzy head and you will have made the summit.

Although the weather was generally good, we got slightly unlucky as the clouds rolled in and scuppered the view, but nevertheless we had the summit to ourselves and a good 30-40 minutes on top to drink in the atmosphere and think about what we’d achieved.

It’s not over until you get down

Summit is not summit unless you get out again. We’d spent 10 hours getting to the top, and whilst descending is naturally quicker, we still had 4 hours of focus and concentration ahead of us, including navigating the rocky Canaleta, the traverse and various other obstacles. But after just short of 14 hours in total, we were back at Camp 3, summit in the bag, adrenaline pulsing. And after a poor night’s rest, we descended to base camp and after one night there, a full walk back out - all the way back down the valley; a mere 8 hours to cap it all off.

We’d made it - mostly safe and sound. Celebratory steaks and Malbec all round!

On the expedition

Some people have asked what it’s like to be on a 20+ day expedition - day to day living, kit lists, and just managing. The account above probably paints a slightly rosier picture than it really is. Kit lists are a whole topic on their own (and will happily put a detailed post together if that’s of interest) but in simplest terms you’ve got around 30kg with you. This is split between your day bag, your mountain bag and your duffle bag and kit logistics on the mountain are important. The mules do a lot of the hard work meaning you’re usually only carrying what you need for the day - around 5kg - 8kg, but there are still heavy carry days. In the upper camps you will be carrying more, especially on days where there’s community carry (e.g., food) so you will be anywhere from 13kg - 18kg (or more.) Superhuman porters are available if you want to lighten the load.

The main difficulty with packing for Aconcagua (and perhaps the reason the gear is so heavy) is that you have to pack for real extremes of climate. Travel clothes aside, the valley and early camps are desert-like - hot & dusty so you need to pack for comfort and coolness; but nights and high camps are cold. Double boots and high-fill down jackets are mandatory for the higher areas. Temps in the valley walk were around 20℃ but nights in base camp were around 0℃ whilst nights in upper camps were -15℃. Factor in wind-chill when outside and there was a whole range of climates to pack for. Rain was rare - but still a threat. The winds were strong - from calm days to gusting to 80km/h-100km/h in places. The biggest weather threat to summit day is wind; people getting lifted up and off by gusts is not uncommon.

The terrain is very rocky which makes the long walks tiring (esp. on the trails that have been destroyed by mules) and pitching tents even more fun - either trying to find or having to clear patches to limit the chance of puncturing your thermorest.

The days are generally long (= tiring) but also don’t discount the oppressiveness of the altitdue/oxygen on your abilty to carry out basic tasks even on rest days in camp. You quickly learn to not bend over at the waist - standing up too fast from e.g., tying your boots is enough to topple some people. You start to measure your acclimatisation on the basis of whether you can get to the toilet cubicle without losing your breath.

On that topic, embrace your pee bottle. The single best way to stay in good shape on the mountain is to drink a lot (of water/tea/juice etc.) - which has the obvious and unfortunate consequence of meaning you need to pee more. And when it’s 3am, -10℃ and dark outside your tent and you’re desperate for a slash, the last thing you want to do is wrap up and hunt the longdrop. The pee bottle (or she-wee, I guess?) is your friend. I avoided it for the first few days but by the end of the trip it was so convenient that it became the go to. Not much can be done about the #2’s though, although you will probably find yourself holding out for as long as possible. Hygiene is therefore important - sanitiser, dry wash, and baby wipes become a way of life; you can’t rely on the showers being working. And in the higher camps there are (a) no facilities and also (b) you’re carrying all your gear; so expect to spend a lot of time in the same pants.

With all of the above you really do need an open-minded can-do don’t-whinge attitude; you chose to be on this trip and it’s on you to make the most of it. We saw too many pampered drama queens where their whole group seemed to spend the whole time complaining at or about each other.

Thoughts and warnings

The achievement is very special and I carry a great sense of pride of having made the summit; not only from the physical challenge but also the mental challenge. A 14 hour summit day is one thing, but tack that at the end of 17-20 days’ acclimatisation, sleeping in tents, with fairly rudimentary facilities and few comforts, and it’s made that much harder.

From our group of 10, only two of the client group made the summit, and the success rate was similar in other groups. So to be one of the few who made the summit is special.

However, I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t left with very mixed emotions of the experience. Aconcagua generally claims a 40% success rate - and the reason for not making the summit is usually attributed to weather (particularly high winds) but I suspect the reality is that most failure comes from lack of preparation, underestimating the requirements and struggling with the altitude.

The emergency helicopter was busy every single day coming and going from every single camp. I would guess though that the usage was split fairly evenly between those being evacuated for actual medical reasons (pulmonary or cerebral oedema, altitude mountain sickness, we know of at least one person who had a heart attack) but also those who underestimated what it meant to be there and just took the easy (albeit expensive) option to get out.

Two days before our summit attempt, a French mountaineer fell from the traverse and is in a critical condition in hospital with a fractured skull and frostbite. A day after our summit, a 32-year old British climber, later identified as Rover Hamilton, fell from pretty much the exact same spot - the very spot I had literally walked over the day before - falling 300m and losing a leg and incurring a serious skull fracture. At time of writing, he is still as far as we know in hospital in Argentina with life-changing injuries. (Apologies for DM link, it’s the only English-version I can find.) Our local guides were involved in the very complicated rescue and the grave look on their faces as they joined us later is etched in my memory. I sat next to another climber on the flight home who had witnessed the Frenchman’s fall. They described it as nothing short of harrowing. Even on our summit day, we saw a guide slip from the traverse, but after cartwheeling a couple of times, somehow saved it and managed to walk away unscathed.

These are the harsh realities of this sport but I fear that as long as Aconcagua is marketed as an ’easy trekking peak’ these sorts of dangers will be wholly unexpected, which in the scheme of things, is ridiculous.

Kilimanjaro is a running joke amongst the guides and experts in Aconcagua, because Kili is not sufficient experience or training for Aconcagua. For example, the use of an ice axe on the mountain is very much optional - and though we were carrying and using them, how many other people on the mountain would have known how to self arrest if they needed to? We witnessed other groups where the guides were affixing crampons to their guests’ feet because they had literally never used them before.

To make matters worse, bigheaded mountaineering showoff Nims Purja was lauding about the camp with his new fangled style of glorified celebrity mountaineering, where, if you pay enough of course, he’ll give you the gold-star treatment, with lavish parties, luxury facilities and helicopters to do all the hard work. Fly in, grab a snap for Insta and bugger off again. It’s irresponsible.

I’m sad to be left with these negative memories of my trip because on the whole it was a fantastic experience. The Horcones valley is stunningly beautiful, the challenge of the whole trip is not to be underestimated and getting to 40m short of 7000m is a great achievement which I’ll treasure forever.

If you’re considering it, please take extra time to really think about it. Most people of the right mindset, fitness and determination could probably do it, but please do not be fooled by the marketing fluff that paints it as being an easy endeavour. Aconcagua is a proper, serious mountain that does not care about you. Climb it with respect and do not underestimate what it involves.

Shout out to our Argentinian fixers/company Grajales and our guides Fernando, Fede and Beti, and their whole crew at Confluencia and Base Camp. Our UK leader was Ade Hawkins and the trip was organised by Jagged Globe, who subsequently dicked me over on the gear I rented from them, grumble grumble.